Primary Authors: Devin Tooma, Vi Dinh; Co-authors: Jessica Ahn, Jade Deschamps, Satchel Genobaga, Annalise Lang, Victor Lee, Reed Krause, Seth White. Oversight, Review, and Final Edits by Vi Dinh (POCUS 101 Editor).

High-risk vascular emergencies like abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and aortic dissection can be fairly prevalent in developed countries. However, when left untreated, they are often fatal – mortality in ruptured AAA is between 85-90% (Kent). What’s more, aortic diseases often present with nonspecific and misleading symptoms (when symptoms are even present), making a speedy diagnosis essential.

When performed properly, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is an invaluable tool to quickly and accurately screen for these life-threatening conditions.

After reading this post, you will be able to:

- Learn how to scan the Aorta using ultrasound

- Obtain Short Axis views of the proximal, mid, and distal abdominal aorta

- Obtain a Long Axis view of the abdominal aorta

- Obtain a Suprasternal Notch View of the thoracic aorta

- Recognize Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) and Aortic Dissection using ultrasound

Table of Contents

Indications for Performing Aorta Ultrasound

You should conduct an ultrasound of the aorta whenever you suspect abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) or aortic dissection.

- The US preventative task force recommends a one-time screening for AAA in male patients between the ages of 65-75 who have ever smoked.

- Male sex and advanced age (≥ 65) are considered risk factors for both AAA and aortic dissection. However, keep in mind that patients with congenital risk factors will commonly present before age 40 (Lederle, Howard).

Below is a table to keep in mind when considering Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) or Aortic Dissection:

| Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) | Aortic Dissection | |

| Pain quality | Constant, intense abdominal, back, pelvic, or flank pain that may radiate to buttocks, groin, or thighs | Acute-onset, severe chest or back pain with ripping/tearing/sharp or stabbing quality |

| Risk factors | Smoking Hypertension Hypercholesterolemia Atherosclerosis & coronary artery disease | Acquired: Hypertension Smoking Third Trimester Pregnancy Amphetamines, cocaine Congenital: Connective tissue disease (Ehler’s-Danlos, Marfan’s) Bicuspid aortic valve |

| Physical Findings | Pain, hypotension, pulsatile abdominal mass (ruptured AAA classic triad) Systolic abdominal bruit Signs of GI bleeding or retroperitoneal hemorrhage | Syncope, hypotension/shock Pulse deficit, systolic BP differential between limbs Aortic regurgitation murmur Neurologic Deficits |

Aorta Ultrasound Preparation

Patient preparation

- The patient should be supine with the head of the bed flat.

- Have patient bend knees, if possible, to help relax the abdominal muscles.

Ultrasound machine preparation

- Transducer:

- Use a Curvilinear probe to examine the abdominal aorta.

- Use a Phased Array probe to obtain the suprasternal notch view.

- Preset:

- Ultrasound Machine Placement:

- Place the machine on the patient’s right side, so you can scan with your right hand and manipulate the ultrasound buttons with your left hand.

Aorta Ultrasound Anatomy

The aorta is divided anatomically into the Thoracic Aorta and the Abdominal Aorta. Each can be further subdivided into three sections.

THORACIC AORTA: spans from the T3-T12 spinal levels, above the diaphragm.

- Ascending Aorta: from the sternal angle to T4/T5.

- Aortic Arch: starts at T4/T5, reaches T3, ends at T4.

- The aortic arch has 3 main branches visible on ultrasound from the suprasternal notch: the brachiocephalic artery, the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery.

- Descending Thoracic Aorta: T4-T12, where it becomes the abdominal aorta after passing through the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm.

ABDOMINAL AORTA: spans from the T12 to L4 spinal levels, below the diaphragm. The proximal and mid abdominal aorta are collectively known as the suprarenal abdominal aorta. The distal abdominal aorta is considered the infrarenal abdominal aorta.

- Proximal Abdominal Aorta: spans from the diaphragm, celiac trunk to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA).

- Mid Abdominal Aorta: spans roughly from the SMA to the level of the renal arteries.

- Distal Abdominal Aorta: spans from the level of the renal arteries to the iliac bifurcation.

For ultrasound, visualizing the abdominal aorta is much more feasible than visualizing the complete thoracic aorta since much of the thoracic aorta is surrounding by lung/air (which ultrasound can’t penetrate through).

Most of this post will go over how to visualize the abdominal aorta all the way to the iliac bifurcation. However, there are parts of the thoracic aorta you can see using the suprasternal view described later on in the post.

Abdominal Aorta Ultrasound Protocol: Short Axis

For the short axis abdominal aorta ultrasound protocol, you will examine the short axis of the abdominal aorta from the celiac trunk down to the iliac bifurcation in 3 main sections: proximal, mid, and distal. You will also measure the aortic diameter in each section.

Step 1: Proximal Abdominal Aorta

In the proximal abdominal aorta, you will distinguish the aorta from the IVC, view the celiac trunk/superior mesenteric artery, and measure the aortic diameter.

Place your probe just below the xiphoid process, slightly left of midline to the patient , with the probe indicator facing the patient’s right/examiner’s left (“9 o’clock”) to obtain a short axis/transverse view of the proximal aorta.

Adjust the depth until the hyperechoic vertebral body and its dense shadow are visible at the bottom of the screen.

- Identify the Aorta, a thick-walled, hypoechoic, pulsatile circle just above the vertebral body, slightly right of midline (patient’s left) on the screen.

- Identify the IVC. It won’t be as circular as the aorta, will lie left of midline on the screen (patient’s right), and is usually collapsible with respirations.

- Keep the probe perpendicular to the abdominal wall for the best short axis view, and accurate subsequent measurements.

- POCUS 101 Tip: If you cannot see these structures, gas in the transverse colon may be blocking your view. Apply constant downward pressure and rock your probe back and forth to displace bowel gas and get your window. If that doesn’t work, try placing your patient in the left lateral decubitus position or attempt the lateral views of the aorta.

Visualize the Celiac Trunk by sliding your probe slightly inferiorly.

- The celiac trunk branches into the common hepatic artery and splenic artery in the “seagull sign” just anterior to the celiac trunk coming off the abdominal aorta.

Visualize the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Slide your probe inferiorly a bit further – it shouldn’t be far, since the SMA originates just distal to the celiac trunk. It will appear as a smaller, circular, hypoechoic structure just anterior to the abdominal aorta.

- In this plane, you may also see the left renal vein between the SMA and the aorta, as well as the splenic vein anterior to the SMA.

- These are the structures implicated in nutcracker syndrome when the left renal vein gets trapped between the aorta and SMA.

Measure the aorta in its widest diameter.

- Freeze the image.

- Take measurements from outer wall to outer wall at it’s widest diameter.

- Obtain both an anteroposterior measurement and a transverse measurement if possible.

Step 2: Mid Abdominal Aorta

- To see the Mid Aorta, slide your probe inferiorly, distally from the SMA, keeping the aorta in view at all times.

Visualize and measure the Mid Abdominal Aorta

- The mid abdominal aorta lacks distinct anatomical landmarks. Occasionally, you will be able to visualize the renal arteries as an inferior boundary for this portion of the exam.

- Measure the mid-aortic diameter once you have obtained a clear view.

Step 3: Distal Abdominal Aorta

- As you scan inferior to the the renal arteries you will approach the distal abdominal aorta.

Visualize and measure the distal aorta.

- The distal abdominal aorta is imaged as the probe approaches the umbilicus.

- This is when the aorta is most superficial, and you may need to decrease your depth.

- Measure the distal aortic diameter once you have obtained a clear view.

Step 4. Abdominal Aortic bifurcation: the common iliac arteries

- Sweep down past the umbilicus until the single aorta becomes two, narrower vessels. This is where the aorta bifurcates into the right and left iliac arteries. Occasionally you may encounter an aneurysm in the iliac artery.

Visualize the common iliac arteries.

Abdominal Aorta Ultrasound Protocol: Long Axis

We recommend obtaining your short axis views and measurements first, then obtaining your long-axis view.

Step 1. Orient the Probe in the Long Axis/Sagittal Plane

- Return to the short axis, subxiphoid view described above, then rotate your probe 90˚ clockwise, with the indicator towards the patient’s head.

- POCUS 101 Tip: center the aorta in the short-axis before rotating. It may be useful to use 2 hands – one to keep your probe centered over the aorta, and the other to rotate the probe.

Step 2. Visualize the Celiac trunk and SMA in the Longitudinal View

- You should see the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) branch off the aorta in the long axis view.

Step 3. Measure the Anteroposterior Diameter

- Be sure to orient your caliper perpendicular to the aortic wall so you don’t overestimate the diameter.

The Cylinder Tangent Effect

Be careful with underestimating the aortic measurements using the long axis approach. This concept is called the Cylinder Tangent Effect and can be seen below where panel (A) shows an ultrasound measurement through the center of the aorta will provide the maximal anteroposterior diameter, whereas panel (B) shows an ultrasound measurement to the side (tangent) of the aorta and will result in a falsely smaller aortic diameter.

Video Summary of Aorta Ultrasound (Short and Long Axis):

Step 4. Using a Lateral Approach (Optional)

When an anterior view is difficult to obtain, an alternate approach is to use the patient’s right or left side to obtain long axis views of the aorta.

From the patient’s Right Side, visualize the liver, IVC, and aorta.

- Place your probe, with the indicator facing the patient’s head, in the right mid-axillary line around the 10-11th intercostal space.

From the patient’s Left Side, visualize the spleen and adjacent aorta.

- Place your probe, with the indicator facing the patient’s head, in the left posterior axillary line around the 7th-8th intercostal space.

Step by Step Suprasternal View of the Aortic Arch

The ultrasound Suprasternal Notch View offers a long-axis view of the thoracic aorta including the ascending aorta, the 3 main branches of the aortic arch (the brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid artery, and left subclavian), and the descending aorta. This view is especially useful when evaluating for a thoracic aortic aneurysm or Type A aortic dissection.

Step 1: Select your Probe.

- Use a Phased Array probe in Cardiac mode. The small footprint of the Phased Array probe allows you to go through the small space of the sternal notch.

Step 2: Position your Patient.

- Your patient should be supine with their neck extended (see below).

- *Placing a pillow under the patient’s shoulders can be helpful.

Step 3. Position your Probe in the Suprasternal Notch.

- Place the indicator towards the patient’s head.

- Rock the tail of the probe superiorly.

- Then, rotate slightly clockwise (15-20˚) towards the patient’s left shoulder. This allows the ultrasound window to align with the trajectory of the thoracic aorta, which crosses from right-to-left as it arches posteriorly.

Step 4. Obtain a Longitudinal View of the Thoracic Aorta.

- This view will show the ascending aorta, the aortic arch with its 3 main branches, and the descending aorta. You may see a transverse view of the right pulmonary artery (RPA) as well.

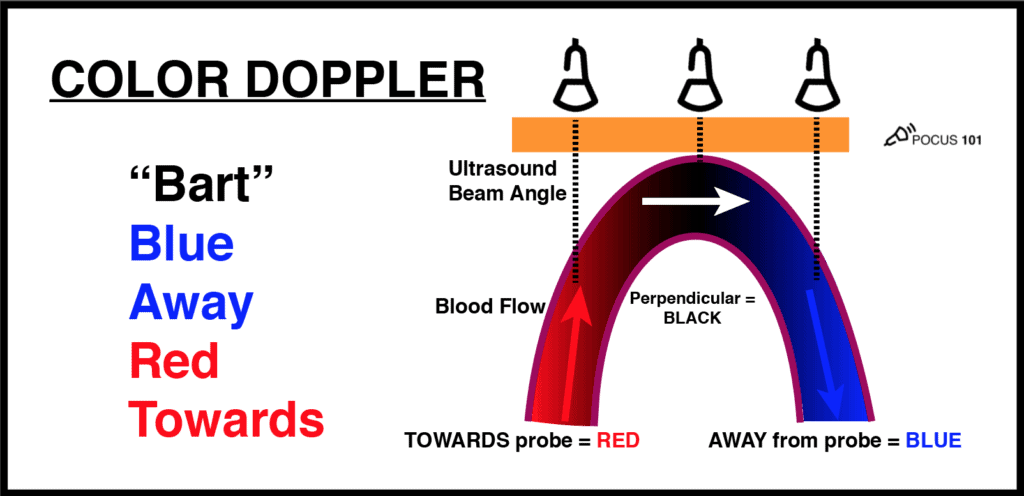

Use color Doppler to assess flow in the thoracic aorta.

- You should see red color Doppler flow (towards probe) in the ascending aorta and blue color Doppler flow (away from probe) in the descending aorta.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) on Ultrasound

Abdominal aortic aneurysms occur when a weakness in the artery’s connective tissue media (usually due to arteriosclerosis) results in a pathologic dilatation of the aorta.

A normal aorta is usually ~2.0cm in diameter. An abdominal aortic aneurysm is defined as: (Mokashi)

- ≥ 3cm diameter for the abdominal aorta or a > 50% increase in the aortic diameter.

- ≥ 1.5cm diameter for the iliac arteries.

Aneurysms can be morphologically classified as either fusiform or saccular. Fusiform aneurysms are symmetrical, circumferential dilatations of a vessel – they are far more common than saccular aneurysms, but less likely to cause symptoms (Faluk). Saccular aneurysms form as asymmetrical outpocketings of the aortic wall.

AAA can be further classified by location as either suprarenal or infrarenal – above or below the renal arteries. Infrarenal AAA is much more common, representing ~85% of cases (Kent).

Ultrasound identification of AAA has a sensitivity and specificity >90% (Fleming), so learning to use it properly can reliably diagnose this life-threatening disease process.

Use the techniques described above to scan the abdominal aorta and measure its diameter in 3 sections (proximal, mid, and distal).

- Keep the aorta in view at all times as you descend, and be careful to note any widening.

- POCUS 101 Tip: a mural thrombus can disguise itself as the outer wall and falsely reduce your diameter measurement. Be sure to measure the outer to outer walls and therefore including the thrombus in the diameter measurement.

Ultrasound findings for Fusiform AAA

A fusiform AAA is seen as widening of the aortic diameter ≥3cm.

Ultrasound Findings for Saccular AAA

A saccular AAA is seen as a hypoechoic pouch off the aortic wall. Notice the images below and how only the anterior abdominal aorta is involved with a saccular appearance in the long axis.

Video Summary of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm using Ultrasound:

Aortic Dissection on Ultrasound

An aortic dissection occurs when a tear in the arterial intima allows blood, under high systolic pressures, to dissect along the arterial media and create a “false lumen” in the aorta. The dissection can travel in an anterograde or retrograde direction.

Unfortunately, aortic dissections are one of the most difficult diagnoses to make since the symptoms can vary from chest pain, abdominal pain, to neurologic deficits depending on what parts of the aorta the dissection involves.

Using the techniques for visualizing the abdominal and thoracic aorta described above, you may detect a free flap in the aortic lumen. The presence of an intimal flap in the aortic lumen is used to diagnose aortic dissection using ultrasound (Siegal).

In the Stanford Classification, dissections are classified into two groups – those that involve the ascending aorta and/or aortic arch (Stanford Type A), and those that originate only distal to the brachiocephalic artery, including the abdominal aorta (Stanford Type B). There is also the DeBakey Classification, which subdivides aortic dissections as class I, II, IIIa, and IIIb as pictured below.

Stanford Classification

- Type A involves the ascending aorta and may progress to involve the aortic arch and thoracoabdominal aorta.

- Type B originates distal to the left subclavian artery and can involve the descending thoracic or thoracoabdominal aorta.

DeBakey Classification

- Type I involves the ascending aorta, arch, and descending thoracic aorta and may progress to involve the abdominal aorta.

- Type II involves only the ascending aorta.

- Type IIIa involves the descending thoracic aorta distal to the left subclavian artery and proximal to the celiac artery.

- Type IIIb originates distal to the left subclavian artery and involves the thoracic and abdominal aorta distal to the celiac artery.

Aortic dissection is the most common in the ascending thoracic aorta: (Larson)

- Ascending aorta: ∼ 65% of cases

- Descending aorta: 20% of cases

- Aortic arch: 10% of cases

- Abdominal aorta: 5% of cases

It is possible to diagnose aortic dissection with transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). It offers a quick diagnosis without having to transfer unstable patients out of the ED. However, transthoracic echocardiography must be used with caution. Although it is highly specific (99-100%), it is not as sensitive (67-80%). Therefore the absence of an intimal flap on TTE does not rule out aortic dissection (Fojtik). CT angiography and transesophageal echo remain the gold standard for diagnosis of aortic dissection.

Below are some examples of aortic dissection seen using transthoracic echocardiography, abdominal aorta ultrasound, and the suprasternal notch views.

Parasternal Long Axis View of Aortic Dissection

This transthoracic parasternal long axis view shows a echogenic dissection flap just distal to the aortic valve.

Suprasternal Notch View of Aortic Dissection

This suprasternal notch view shows an aortic dissection involving the aortic arch and the brachiocephalic and left common carotid artery. This particular patient presented with unilateral right sided weakness.

Descending Aorta View of Aortic Dissection

Aorta ultrasound, is a quick way to see if the aortic dissection involves the abdominal aorta.

Aortic Regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation in aortic dissection will be seen as retrograde diastolic blood flow from the aortic arch, seen with Doppler (Diebold).

References

- Solomon, C., Kent, K. (2014). Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms New England Journal of Medicine 371(22), 2101-2108. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp1401430

- Lederle, F., Johnson, G., Wilson, S., Chute, E., Littooy, F., Bandyk, D., Krupski, W., Barone, G., Acher, C., Ballard, D. (1997). Prevalence and Associations of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Detected through Screening Annals of Internal Medicine 126(6), 441. https://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00004

- Fleming, C., Whitlock, E., Beil, T., Lederle, F. (2005). Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Best-Evidence Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Annals of Internal Medicine 142(3), 203. https://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-3-200502010-00012

- Faluk M, De Jesus O. Aneurysm, Saccular. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 30, 2020.

- Mokashi, S.A., Svensson, L.G. Guidelines for the management of thoracic aortic disease in 2017. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 67, 59–65 (2019). https://0-doi-org.catalog.llu.edu/10.1007/s11748-017-0831-8

- Howard, D., Banerjee, A., Fairhead, J., Perkins, J., Silver, L., Rothwell, P., Study, O. (2013). Population-Based Study of Incidence and Outcome of Acute Aortic Dissection and Premorbid Risk Factor Control: 10-Year Results From the Oxford Vascular Study Circulation 127(20), 2031-2037. https://dx.doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.112.000483

- Fojtik, J., Costantino, T., Dean, A. (2007). The diagnosis of aortic dissection by emergency medicine ultrasound The Journal of Emergency Medicine 32(2), 191-196. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.07.020

- Larson EW, Edwards WD. Risk factors for aortic dissection: a necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53(6):849-855. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(84)90418-1

- Siegal EM, Acute Aortic Dissection. J. Hosp. Med 2006;2;94-105. doi:10.1002/jhm.69

- Diebold, B., Peronneau, P., Blanchard, D., Colonna, G., Guermonprez, J., Forman, J., Sellier, P., Maurice, P. (1983). Non-invasive quantification of aortic regurgitation by Doppler echocardiography. Heart 49(2), 167-173. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.49.2.167

- Lema, P., Kim, J., James, E. (2017). Overview of common errors and pitfalls to avoid in the acquisition and interpretation of ultrasound imaging of the abdominal aorta Volume 5(), 41 – 46. https://dx.doi.org/10.2147/jvd.s124327

If there is a mass (about 8 to 10 cm) around the abdominal aorta can an ultrasound see if the wall behind the mass is not thinning or ruptured? Also, can a ultrasound of the aorta show problems (having the mass still there) in other parts of the aorta and show if the blood flow is normal?

Thank you

James

Hi James this will depend on exactly where the mass is located and how much bowel is around the area. If there is a lot of bowel gas it may inhibit seeing a mass. But in general, a CT scan would be better to evaluate an abdominal mass. POCUS is usually just to see AAA present, yes or no. but sometimes you may catch other things if you look around.

This is very helpful, thank you so much for your hard work!

Thanks so much Hieu for the kind words!

[…] Ultrasound of the week […]